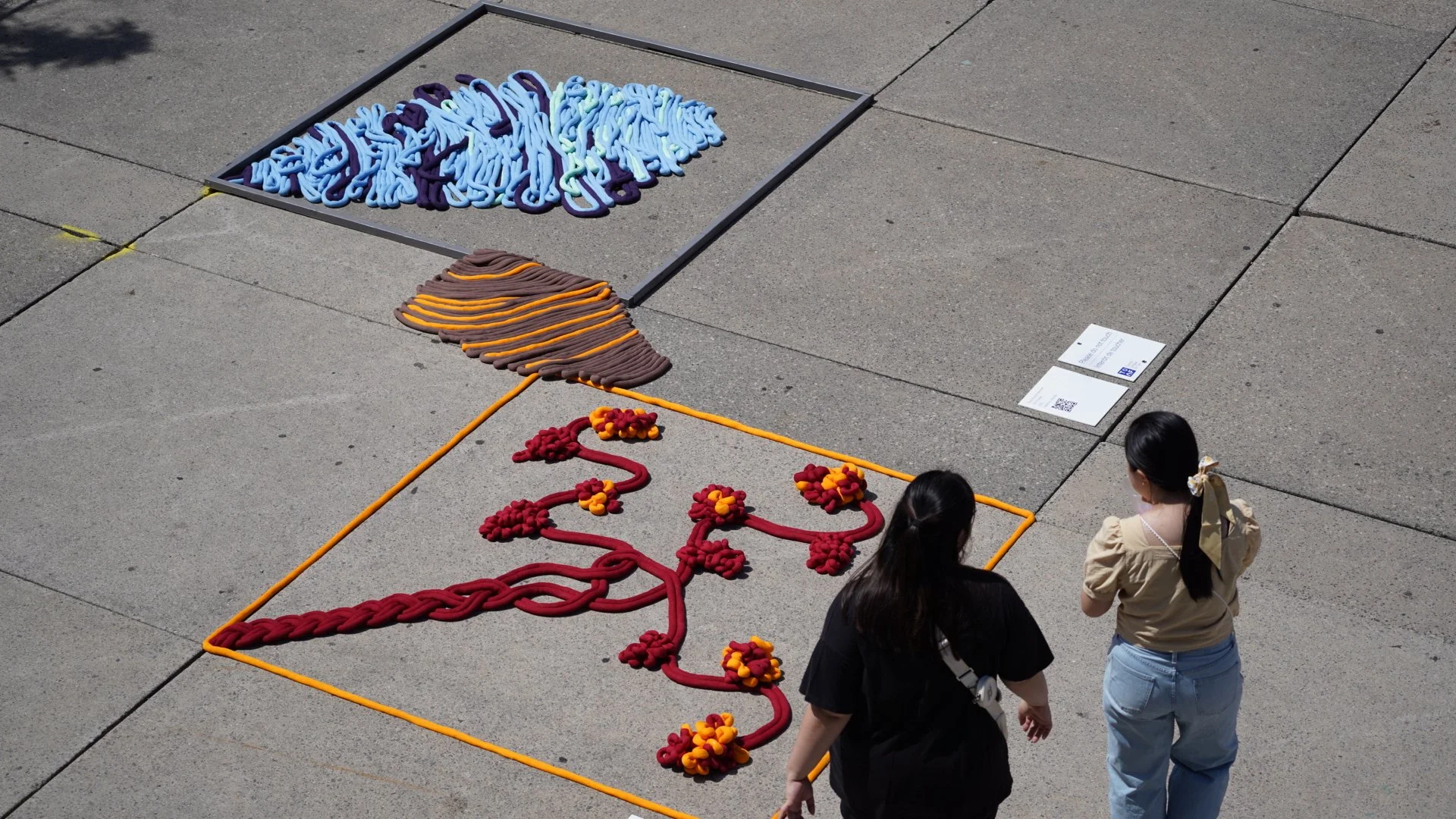

105 Threads draws on Palestinian embroidery and history to ask questions about belonging, displacement, and erased histories in today’s Toronto.

Linked to the imagined archival story of Faiza and Ibrahim Al-Khayyat, enlarged strands of ‘thread’ spanned concrete slabs in Nathan Phillips Square from July 7-9, 2023.

FAIZA and Ibrahim “Abe” AL-KHAYYAT WERE A PALESTINIAN COUPLE THAT arrived in Toronto at the end of the nineteenth century, settling IN ST. JOHN’S WARD. THEIR SMALL EMBROIDERY BUSINESS WAS DEMOLISHED WITH THE REST OF THE WARD NEIGHBOURHOOD TO MAKE WAY FOR NATHAN PHIlLIPS SQUARE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF DOWNTOWN TORONTO. THEIR BURIED EMBROIDERY WORKS, WHICH GREW INCREASINGLY ABSTRACT IN THEIR EXILE, LIE BENEATH THE CONCRETE IN THE VERY SPOT OF THE INSTALLATION PIECE 105 THREADS.

palestinian embroiderers in toronto’s ward

The young Khayyat couple, originating from peasant farming families in the central Palestinian region of Bethlehem, were expert embroiderers whose specialized works were sold modestly across the region before their migration to North America.

Palestinian embroidery at the time was a way for villagers, peasants, and Bedouin to express regional identity, age, and status, and was rarely made or worn by elite classes. In nineteenth century Bethlehem, common motifs included animals like the scorpion, plants such as the cypress tree, local crops like the chickpea, tools like the mill wheel, and symbols like the eight-pointed star of Bethlehem, based on Canaanite myths of the meeting between the deity Astarte (Evening Star) and the Moon. The couple and their craft were distinguished in two ways. First, while embroidery at the time was exclusively practiced by women, Ibrahim had learned to embroider from a young age and worked alongside his wife. Second, the Khayyats eschewed many classic embroidery patterns, creating their own motifs based on their lives and stories of travellers visiting Bethlehem from Greater Syria and beyond. They developed new motifs that rejected the geometric square and rectangle grid common of cross stitching, finding new ways to represent the land in embroidery.

exile and migration

Under Ottoman rule, a series of reforms in the 1800s required Palestinian farmers to register their land. Like many fellahin, or peasants, the Khayyats did not register out of mistrust for the regime and a fear of higher taxation. As a result, ruling families of the effendi class claimed ownership of vast swaths of land and even sold it out from under peasant families. Having lost their land, home, and primary source of income, the Khayyats traveled to Chicago shortly after the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, hoping to build a name for themselves as embroiderers.

A large Palestinian contingent was present at the Exposition, selling handicrafts, textiles, and souvenirs from the Holy Land. The success of Palestinians at the Exposition would later spur a wave of Palestinian, Syrian, and Lebanese migrants to the United States, including the Khayyats (until 1921, when U.S. immigration quotas halted Arab immigration in favor of European migrants). At the time, Palestinian immigrants were almost exclusively male, providing for their families from abroad, before returning to Palestine to retire. The Khayyats, not wishing to return to their landless internal displacement, chose to remain, but quickly left Chicago for Detroit.

traveling embroidery

Faiza immediately went to work embroidering dresses, belts, and headdresses, and Ibrahim began to sell their products door to door as they traveled East to Detroit. This was not unusual for Arab immigrants at the time, who largely either worked in factories or sold goods door-to-door. In fact, the travel involved in peddling led to small Arab communities in nearly every U.S. state by 1900.

During their travels east, they spent a period of time with the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi (NHBP), whose lands had historically stretched across the state colonized as Michigan, from Grand Rapids to Detroit, and south to northern Indiana. In 1838, the NHBP were forcibly removed from their lands in an operation known as the Trail of Death, and in 1845, the Pine Creek Indian Reservation was established near Fulton, Michigan. The Khayyats came to a rest in Pine Creek after finding success trading customized embroidery. There, they developed new motifs related to plants that they recognized from home among the Great Lakes community, including staghorn sumac and wild sage, and others that were new to them, including wild rice.

In Detroit, the Khayyats lived for a few years among a small community of less than 50 Lebanese Maronites who worked as peddlers and shopkeepers. Here they first saw Lake Erie, which struck them as a saltless sea rather than a lake. Seduced by its waters, the couple eventually made their way across Erie by steamer to Ontario, and went north by train to Toronto.

in the ward

The Khayyats arrived in Toronto and found their way to a poor neighbourhood called St. John’s Ward, which ran from University Avenue to Yonge Street. At the end of the century, waves of immigrants were arriving in the Ward, including Irish refugees that had escaped the Great Famine, African Americans who had traveled north through the Underground Railroad, Italian trade and craftspeople, and Jewish migrants from across Russia and Eastern Europe. The Ward was also known as having a dynamic street life, despite being considered a slum due to severe overcrowding and poor housing conditions. The Khayyats settled there, finding solace among the diversity of the displaced population.

Faiza and Ibrahim rented a small hut constructed on the side of a house and opened a small embroidery business. They refused to work as tailors, insisting on selling their highly ornate embroidery, and their business was categorically unsuccessful. They did not find a willing market in the working-class Ward, and their small home filled with unsold sheets of embroidered chest pieces, belts, thobes (traditional dresses), tapestries, and other textiles.

The deplorable conditions in the Ward were an intentional result of landlord greed and city neglect. As downtown creeped towards the Ward, landlords knew that property prices would spike, and for years they refused to spend money on repairs while tenants crammed into rooms, basements, and attachments, often without plumbing or lighting. Unsanitary conditions prompted discrimination from other Torontonians, who blamed the residents for their own poverty. In the early twentieth century, hundreds were evicted to make way for government buildings. As the city took hold of the Ward, Jewish and Italian communities traveled west towards Spadina, leaving Old Chinatown, one of the last remaining areas of the Ward, and incidentally, home to the Khayyats.

105 years ago

Amid anti-immigrant sentiment, growing evictions, and as the First World War came to an end, the Khayyats considered returning to Palestine in 1918. They considered that the fall of the Ottoman Empire may allow them to reclaim their ancestral lands, but as the United Kingdom and France divided the Middle East between them, initiating what would become 105 years of colonial rule in Palestine, their faith dwindled. A few years later, the Khayyats heard word from family members that their land had been sold to Zionist settlers gathering in Mandate Palestine.

Little is known about the Khayyat’s life in Old Chinatown, other than that they remained there for over five decades, never having children and continuing to peddle their embroidery wherever possible. Their permanent exile marked their lives, and their embroidery work grew increasingly abstract, disorganized, and repetitive.

demolished and disappeared

Toronto’s Old Chinatown emerged in the Ward in the early 1900s, established by Chinese labourers who had been brought to Canada to build the railroads. In 1923, its growth halted when Canada implemented the Exclusion Act banning Chinese immigrants. Amid growing hostility, Toronto’s Old Chinatown was targeted for demolition in the 1950s, including the plot where the Khayyats lived and sold their embroidery. By the 1960s, the southern half of Old Chinatown was razed to the ground and in 1965 Nathan Phillips Square and New City Hall were opened in their place.

Eyewitness accounts noted that at the time of its demolition, their small home was full to the ceiling with rolls of unsold embroidered textiles, but that the couple was nowhere to be found. Their later works obsessed over elements of life in Turtle Island that reminded them of home, including the vast waters of Lake Ontario and Erie, in their different hues, and the sumac trees bordering every roadway in Toronto. All records of the Khayyat couple disappeared with the demolition of their home, which lies beneath the exact location of the installation piece 105 Threads.

Palestinian Embroidery; Arab immigration; Staghorn Sumac; The Trail of Death; Lake Erie; St. John’s Ward; Lake Ontario; Old Chinatown; Toronto history; Nathan Phillips Square